The 'City By the Bay' Fights WW2: A Western Hub for Troops & War Production

Wartime San Francisco: La Verne Bradley, 1943 The impact of San Francisco at war comes like the kick of a big gun to anyone who hasn't seen it since Pearl Harbor. Fighting men have taken over the city, as did the Vigilantes of old. They have geared its life, colored its streets, inspired its people. Troops, guns, bayonets, motor unites, ships, supplies --- on the move. Soldiers, marines, mines, nets, bayonets, barrages, barbed wire on guard. It is absolutely forbidden to cross this line. No cameras or field glasses, please. 'Men in uniform welcome!'

If for a moment you lose yourself in old smells, sounds, memories, fighter planes come screaming down the skyline and, lifting you right up on your toes, almost clip of the top of the old Ferry Building to remind you that this is 1943 and a city at war! Helmeted, bullet-belted patrols guard every bridgehead, river mouth, slip landing, seemingly harmless road entrances, tunnels, railroad crossings, and barren hills.

You hear the rivet guns and hammer presses of shipyards; the screech of braked wheels grating on steel rails as oil moves in thousands of tank cars from refineries; the roar of blast furnaces; the thunder of Army trucks seeding by under guard 10, 20, 30 filled with soldiers. You see hills being leveled as giant shovels slap at their sides like fly swatters. You see new towns rising from reclaimed swaps and dust holes.

You look across fields of barrage balloons suspended awkwardly in midair like tall-heavy sausages. Finally, you look across to the Gold Gate where, against a low sun, a line of blue, heavily burdened ships is slowly steaming out. The Navy has here the Mare Island Navy Yard, the new Alameda Naval Air Station, a blimp base, supply depots, dry docks, and training centers.

All other activities are subordinated to the moving of troops and supplies, defending the harbor, maintaining port facilities, and supporting new war industries. During the early months of the war San Francisco cleared more military supplies than all other United States ports combined. In peacetime 25,000 replacement troops cleared this port every year to relieve men garrisoned overseas. Today, figures withheld, one can only watch and wonder at the numbers of soldiers in full kit swing onto rows of dark blue ships.

Laughing, sweating, swearing, shoving, they pour over gangways and packing boxes. The fog brushes by like wisps of steam. The low basses of the foghorns repeat their monotones on the Bay. The smell of fish and sea rises from the waterfront. Some of these soldiers have had a few days or hours in town. Others, fresh from staging areas, have just pulled off a blacked-out train.

Only a few familiar objects tell them where they are. Nothing tells them where they are going. For the thousands of men who pass through that Gold Gate, it is their last glimpse of America for many months; it holds all their parting memories.

But San Francisco Bay doesn't belong entirely to the Army. Mare Island was the first spot in America to get the news about Pearl Harbor. With its powerful radio station, it intercepted Kimmel's historic message to the Pacific Fleet which ended with 'this is no drill' The news was flashed to Washington and read to President Roosevelt by Secretary Knox before and official communique reached the Navy Department.

Across the bay in Richmond, more than 747 vessels were built in the four Richmond Kaiser Shipyards during World War II; a feat not equaled anywhere else in the world, before or since. All of Kaiser's shipyards together produced 1,490 ships, which amounted to 27 percent of the total U.S. Maritime Commission construction. These ships were completed in two-thirds the amount of time and at a quarter of the cost of the average of all other shipyards. The Liberty Ship Robert E. Perry was assembled in less than five days as a part of a special competition among shipyards; but by 1944 it was only taking the astonishingly brief time of a little over two weeks to assemble a Liberty ship by standard methods.

Henry Kaiser and his workers applied mass assembly line techniques to building the ships. This production line technique, bringing pre-made parts together, moving them into place with huge cranes and having them welded together by "Rosies" (actually "Wendy the Welders" here in the shipyards), allowed unskilled laborers to do repetitive jobs requiring relatively little training to accomplish. This not only increased the speed of construction, but also the size of the mobilization effort, and in doing so, opened up jobs to women and minorities.

During WWII, thousands of men and women worked in this area everyday, in very hazardous jobs. Actively recruited by Kaiser, they came from all over the United States to swell the population of Richmond from 20,000 to over 100,000 in three short years. For many of them, this was the first time they worked and earned money. It was the first time they were faced with the problems of being working parents--finding daycare and housing. Women and minorities entered the workforce in areas previously denied to them. However, they still faced unequal pay, were shunted off into 'auxiliary' unions and still had to deal with day-to-day prejudice and inequities. During the war, there were labor strikes and sit-down work stoppages that eventually led to better conditions. As one African American Rosie commented about the progress of labor and civil rights during this time, while huge gains had to wait for the post-war civil rights movement, the Home Front did 'begin to shed light on America's promise.'

During WWII, President Franklin D. Roosevelt banned the production of civilian automobiles to ensure that America was prepared for the battle ahead. At that time, the Ford Richmond Assembly Plant switched to assembling jeeps and putting the finishing touches on tanks, half-tracked armored personnel carriers, armored cars, and other military vehicles destined for the Pacific Theater.

By July of 1942, military combat vehicles began flowing into the Richmond plant for final processing before being transported through the deep-water channel to war zones. The 'Richmond Tank Depot,' as the Ford plant was then called, helped keep American soldiers supplied with up-to-the-minute improvements to their battle equipment.

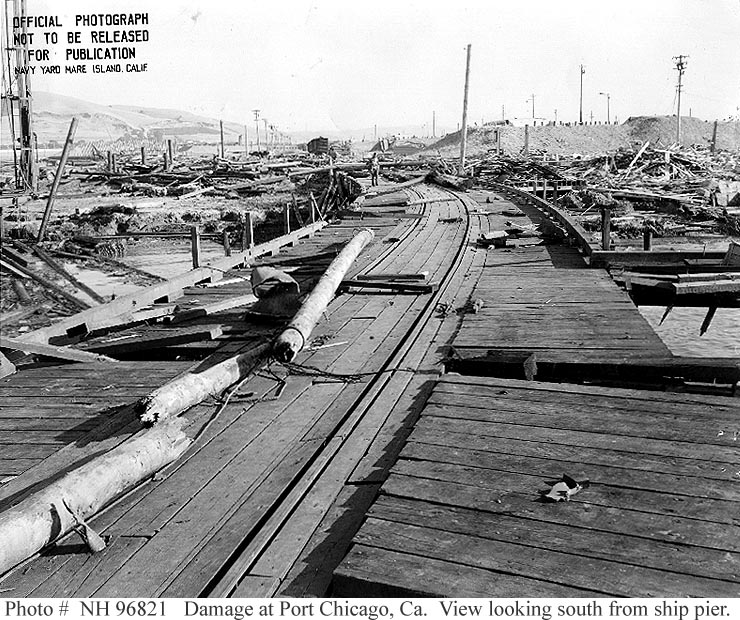

Another event in the bay area that attracted nationwide attention was the disaster at Port Chicago in Contra Costa County. The Port Chicago disaster was a deadly munitions explosion of the ship SS E. A. Bryan that occurred on July 17, 1944, at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California, United States. Munitions detonated while being loaded onto a cargo vessel bound for the Pacific Theater of Operations, killing 320 sailors and civilians and injuring 390 others.

The enlisted men were leery of working with deadly explosives but were told by officers that the larger munitions were not active and could not explode—that they would be armed with their fuzes upon arrival at the combat theater. Handling of larger munitions, such as bombs and shells, involved using levers and crowbars from boxcars, in which they were packed tightly with dunnage-- lifting the heavy, grease-coated cylinders, rolling them along the wooden pier, packing them into nets, lifting them by winch and boom, lowering the bundle into the hold, then dropping individual munitions by hand a short distance into place. The dangerous system and lies told by the officers resulted in the greatest munitions tragedy in American History.

A month after the explosion, unsafe conditions inspired hundreds of servicemen to refuse to load munitions, an act known as the Port Chicago Mutiny. Fifty men--called the "Port Chicago 50"--were convicted of mutiny and sentenced to 15 years of prison and hard labor, as well as a dishonorable discharge. Forty-seven of the 50 were released in January 1946; the remaining three served additional months in prison.

During and after the trial, questions were raised about the fairness and legality of the court-martial proceedings. Owing to public pressure, the United States Navy reconvened the courts-martial board in 1945; the court affirmed the guilt of the convicted men.

Widespread publicity surrounding the case turned it into a cause célèbre among Americans opposing discrimination targeting African Americans; it and other race-related Navy protests of 1944–45 led the Navy to change its practices and initiate the desegregation of its forces beginning in February 1946. In 1994, the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial was dedicated to the lives lost in the disaster.